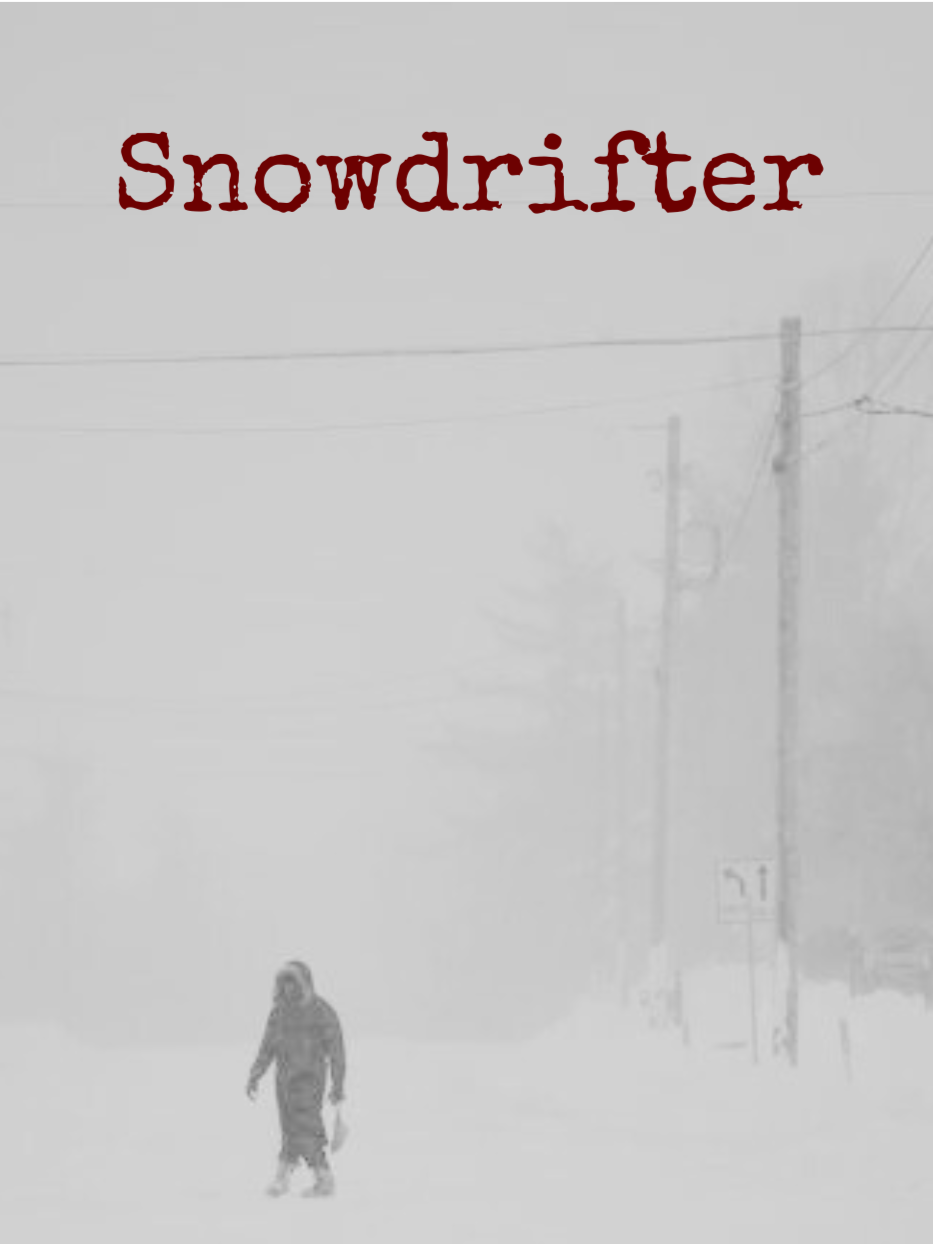

In town, powder sweeps over trucks, tractors, and all other vehicles left ungaraged. Many of them have been buried entirely for days, and the relentless wind only pushes snow even higher, stretching drifts up the sides of homes in a sort of icy game of rooftop tag. Gusts have been averaging anywhere from twenty to sixty-five miles per hour, according to the local news, and several tree branches have come down, taking out power lines across the area. Royalton has been without power for nineteen hours.

Fortuitously, Silas believed the weatherpersons and talking heads. He prepared, or he thought he prepared. He thought he bought plenty of gas for the generator, but now he’s unsure. He’s certain food is not a problem, though. His pantry rivals those in the bunkers of even the most well-organized doomsday preppers, and he has enough toilet paper to make all of those Covid-19 tissue-hawks years back look like amateurs. Of course, he couldn’t take his chances on the necessities this time. Unlike the October storm, he no longer lives alone.

In late May of last year, Silas’s 68-year-old mother, Beverly, suffered a stroke, rendering her unable to speak more than a handful of words and incapable of making due by herself. As her only son, Silas moved back into the family duplex to care for her. The arrangement is fine. It doesn’t put a cramp in his style since his style consists of going to work, coming home, and little else.

And Beverly is happy to stay out of the way, residing in the attic, only accessible by way of a dropdown ladder in the hallway ceiling. It’s not as harsh as it sounds. The attic is a separate studio apartment, virtually. It’s absent a kitchen but has everything else one needs to get by, including a loveseat parked in front of a decent television, a twin bed, toilet, and a small walk-in shower, complete with a seat and safety rail that Silas installed specifically for her.

Everyone appreciates feeling needed sometimes, and Silas supposes he’s no exception. Perhaps that’s why he never so much as scoffed at the chore of installing the handrail and seat, not as he shucked tools and materials up the ladder, nor even when an elbow joint loosened, springing a small flood in the kitchen below. Any frustrations that arose fleeted quickly, and Silas is sure his good intentions laid the foundation for his patience. What lived beneath the surface, however, was a level of selfishness in his actions. While it sounds trite and unimaginative, Silas took on the arrangement to be close to his mother during her inevitably waning days, naturally, but mostly, he supposes he did it just to feel like he mattered to someone again.

Silas wondered often why he had acted in all of his relationships as though they’d ended before they even started. Introversion is healthy, he supposes, certainly in moderation, but he had been too emotionally juvenile to realize that his insecurities were driving him then. And he still doesn’t know if his introversion had been his guardian or destroyer over the years, but he does know that the traditional wife-kid-dog route never felt authentic to him. It fit him like a baggy suit, tailored for someone else, someone bigger than him. And maybe Ash could see that, even early on in their relationship.

There’s no more sense in fretting over her, though, he’s convinced himself he’s too damaged to be loved, and under this influence, believes that he navigated away from family life rightfully, whether he did so consciously or not. There is little regret, but there is certainly no one around much, either. And recently, he’s been questioning whether caring for the old woman was his way of keeping company or avoiding it.

Of course, the duo has their difficulties; the ones you might imagine would be inherent in their situation. And it doesn’t help that Beverly only speaks a few colorful phrases like “shit” and “fuck you,” or that “speaks” is a generous word for a more suitable term like, “grumbles.” She was a damn coarse woman in her prime, and a long life filled with disappointment and loss stacked on top of a grim health condition has not softened her edges. She doesn’t always mean to cuss at her only son — the only one who has been there for her — day after day, night after night. But these are easy, one-syllable utterances for a stroke victim. The mother and son team have worked it out tonally.

Still, there are times when a mostly healthy, introverted man might have fantasies of aloneness. Oftentimes, the fantasies are nothing more than dreaming of total privacy, even if to fulfill no other desire than watching pornography with the volume on again. Beverly has a lot of impediments, but her hearing is as clean as it’s ever been. Other times, the fantasies are a little darker. Silas supposes he dreams of nothing too far out of the ordinary, but if he’s being honest with himself, there are times he wishes he had a touch more bravery; times he wishes he could be as ruthless as say, Mr. Hammy had been all those years ago…